________________________________________________________________________________

The Jimani Lounge, The History of The Upstairs Lounge

Upstairs Lounge Fire CBS Network News Coverage, Monday, June 25, 1973, (Fire occurred Sunday evening, June 24, 1973)

Uploaded on Sep 4, 2007

This is the only national news coverage of the deadliest fire in the history of New Orleans. This mass murder took place in a gay bar in 1973 so the media outside of New Orleans pretty much ignored the unprecedented loss of life.On the last Sunday in June, 1973, a gay bar in New Orleans called the UpStairs Lounge was firebombed, and the resulting blaze killed 32 people. At the time, the bar had recently served as the temporary home for the fledgling New Orleans congregation of the Metropolitan Community Church. Founded in Los Angeles in 1968, the MCC was the nation’s first gay church.

No one was ever charged with the crime, but there was a prime suspect.

It was the third fire at a MCC church during the first half of 1973, following earlier arsons in Nashville and Los Angeles. The church’s Los Angeles headquarters was destroyed on January 27, five days after the U.S. Supreme Court announced its momentous decision in the case of Roe v. Wade.

That Sunday was the final day of Pride Weekend, the fourth anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising of 1969. Yet there was still no Gay Pride Parade in New Orleans. Almost two dozen gay bars dotted the French Quarter, but gay life in the city remained largely underground.

Located on the second floor of a three-story building at the corner of Chartres and Iberville Streets, the UpStairs Lounge had only one entrance, up a wooden flight of stairs. Nearly 125 regulars had jammed the bar earlier that afternoon for a free beer and all you could eat special. After the free beer ran out, about 60 stayed, mostly members of the MCC congregation.

Original site of the UpStairs Lounge at 141 Chartres Street as it looked in Spring, 2008.

Before moving worship services to their pastor’s home earlier in June, congregation members had been holding services at the UpStairs on Sundays. But the bar was still a spiritual gathering place. There was a piano in one of the bar’s three rooms, and a cabaret stage. Members would pray and sing in this room, and every Sunday night, they gathered around the piano for a song they had adopted as their anthem, United We Stand, by The Brotherhood of Man.

United we stand, divided we fall...They sang the song that evening, with David Gary on the piano, a professional pianist who played regularly in the lounge of the Marriott Hotel across the street. The congregation members repeated the verses again and again, swaying back and forth, arm in arm, happy to be together at their former place of worship on Pride Sunday, still feeling the effects of the free beer special.

And if our backs should ever be against the wall,

We’ll be together…

Together...you and I.

At 7:56 pm a buzzer from downstairs sounded, the one that signaled a cab had arrived. No one had called a cab, but when someone opened the second floor steel door to the stairwell, flames rushed in. An arsonist had deliberately set the wooden stairs ablaze, and the oxygen starved fire exploded. The still-crowded bar became an inferno within seconds.

The emergency exit was not marked, and the windows were boarded up or covered with iron bars. A few survivors managed to make it through, and jumped to the sidewalks, some in flames. Rev. Bill Larson, the local MCC pastor, got stuck halfway and burned to death wedged in a window, his corpse visible throughout the next day to witnesses below.

This photo appeared in wire stories about the tragedy. Rev. Larson's body was not removed from the window throughout the initial investigation, and symbolized the city's uncaring attitude towards the mostly gay victims.

Bartender Buddy Rasmussen led a group of fifteen to safety through the unmarked back door. One of them was MCC assistant pastor George "Mitch" Mitchell. Then Mitch ran back into the burning building trying to save his partner, Louis Broussard. Their bodies were discovered lying together.

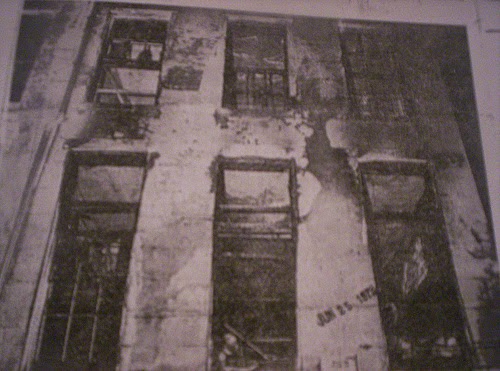

View of the building from Iberville Street in the fire's aftermath. Police are visible in the far right window.

29 lives were lost that night, and another three victims later died of injuries from the fire. The death toll was the worst in New Orleans history up to that time, including when the French Quarter burned to the ground in 1788. It was almost assuredly the largest mass murder of gays and lesbians to ever occur in the United States.

Yet the city of New Orleans tried mightily to ignore it. Public reaction was grossly out of proportion to what would have happened if the victims were straight. The fire exposed an ugly streak of homophobia and bigotry. It was the first time New Orleans had to openly confront the existence of its own gay community, and the results were not pretty.

Initial news coverage omitted mention that the fire had anything to do with gays, despite the fact that a gay church in a gay bar had been torched. What stories did appear used dehumanizing language to paint the scene, with stories in the States-Item, New Orleans’ afternoon paper, describing “bodies stacked up like pancakes,” and that “in one corner, workers stood knee deep in bodies…the heat had been so intense, many were cooked together.” Other reports spoke of “mass charred flesh” and victims who were “literally cooked.”

The press ran quotes from one New Orleans cab driver who said, “I hope the fire burned their dress off,” and a local woman who claimed “the Lord had something to do with this.” The fire disappeared from headlines after the second day.

A joke made the rounds and was repeated by talk radio hosts asking, “What will they bury the ashes of queers in? Fruit jars.” Official statements by police were similarly offensive. Major Henry Morris, chief detective of the New Orleans Police Department, dismissed the importance of the investigation in an interview with the States-Item. Asked about identifying the victims, he said, “We don’t even know these papers belonged to the people we found them on. Some thieves hung out there, and you know this was a queer bar.”

In the days that followed, other churches refused to allow survivors to hold a memorial service for the victims on their premises. Catholics, Lutherans, and Baptists all said no.

William “Father Bill” Richardson, the closeted rector of St. George’s Episcopal Church, agreed to allow a small prayer service to be held on Monday evening. It was advertised only by word of mouth and drew about 80 mourners. The next day, Richardson was rebuked by Iveson Noland, the Episcopalian bishop of New Orleans, who forbade him to let the church be used again. Bishop Nolan said he had received over 100 angry phone calls from local parishioners, and Richardson’s mailbox would later fill with hate letters.

Eventually, two additional ministers offered their sanctuaries – a Unitarian church, and St. Mark’s United Methodist Church in the French Quarter. It was here that a July 1 memorial service was held attended by 250 people, including the state's Methodist bishop, Finis Crutchfield, who would die of AIDS fourteen years later at age 70.

Although called on to do so, no elected officials in all of Louisiana issued statements of sympathy or mourning. Even more stunning, some families refused to claim the bodies of their dead sons, too ashamed to admit they might be gay. The city would not release the remains of four unidentified persons for burial by the surviving MCC congregation members. They were dumped in mass graves at Potter’s Field, New Orleans' pauper cemetery. No one was ever charged with the crime, and it remains unsolved.

Thirty-five years from now, let’s hope we look back and wonder what the fuss over gay marriage was all about. But history won’t remember anti-gay bigots kindly, whether they were cowardly murderers like the unknown arsonist who firebombed the UpStairs Lounge in 1973, the people of New Orleans who callously disregarded a fire that took 32 of their fellow citizens' lives because it happened at a gay bar, or today’s misguided opponents of same-sex marriage.

In Memory (List of victims from The UpStairs Fire: 25th Memorial Service)

Partners Joe William Bailey & Clarence Josephy McCloskey, Jr. perished together. McCloskey's sisters and two nieces attended the Memorial Service. His niece, Susan, represented McCloskey in the Jazz Funeral.

Duane George "Mitch" Mitchell, assistant MCC pastor. He had escaped through the emergency exit with a group led by bartender Douglas "Buddy" Rasmussen, but ran back into the burning building trying to save his partner, Louis Horace Broussard. Their bodies were discovered lying together.

Mrs. Willie Inez Warren of Pensacola later died from burns suffered in the fire. Her two sons died inside the bar, Eddie Hosea Warren and James Curtis Warren.

Pastor of the MCC, Rev. William R. Larson, formerly a Methodist lay minister.

Dr. Perry Lane Waters, Jr., a Jefferson Parish dentist. Several victims were his patients and were identified by his x-rays.

Douglas Maxwell Williams

Leon Richard Maples, a visitor from Florida.

George Steven Matyi

Larry Stratton

Reginald Adams, Jr., MCC member, formerly a Jesuit Scholastic. Partner of entertainer Regina Adams.

James Walls Hambrick, who had jumped from the building in flames, died later that week.

Horace "Skip" Getchell, MCC member.

Joseph Henry Adams

Herbert Dean Cooley, UpStairs Lounge bartender and MCC member.

Professional pianist, David Stuart Gary.

Guy D. Anderson

Luther Boggs, teacher, who died two weeks later. Notified while hospitalized with terrible burns that he had been fired from his job.

Donald Walter Dunbar

Professional linguist, Adam Roland Fontenot, survived by his partner, bartender Douglas "Buddy" Rasmussen, who led a group to safety.

John Thomas Golding, Sr., member of MCC Pastor's Advisory Group.

Gerald Hoyt Gordon

Kenneth Paul Harrington, Federal Government employee.

Glenn Richard "Dick" Green, Navy veteran.

Robert "Bob" Lumpkin

Four men were buried in Potter's Field: Ferris LeBlanc (later indentified), and three persons only identified as Unknown White Males. The city refused to release these bodies to the MCC for burial.

A sidewalk memorial plaque now rests outside the building, dedicated on the fire's 30th anniversary in 2003.

________________________________________________________________________________

http://outandaboutnewspaper.com/article.php?id=2022 dead link

http://www.outandaboutnashville.com/story/new-orleans-upstairs-lounge-still-burns#.U-8povldVas

November 1, 2007, Out & About Nashville, New Orleans' Upstairs Lounge still burns, by Cole Wakefield,

A forgotten tragedy smolders in our community's past

It is June 24, 1973, and you are about to enter your favorite spot in all of New Orleans. You glance around, just in case, before you open the door to the stairway and make your way up to the bar.

As always you exchange a friendly hello with the bartender, Buddy, and give his partner Adam a hug. On your way over to your regular spot by the white baby grand, you are stopped by Jimmy who is sitting at a table with his brother Eddie and an older woman. Jimmy and Eddie are excited to introduce you to their mother who has joined them for an evening of family fun. You think about how wonderful is must be for those two gay boys to be able to bring their mother out to a ‘queer’ bar. Just then you hear a loud laugh and know that Rev. Bill Larson of the local MCC must be around. Turns out almost the entire congregation is here, thanking a benefactor for the air conditioner he had recently donated. It’s just another night at The Upstairs Lounge and then someone rings the door buzzer.

It rings again, and again, and again. Finally Buddy grows annoyed and asks someone to go downstairs and see who it is. You are only half-way paying attention as your friend Luther gets up to open the steel door. You are startled as a large fireball knocks Luther to the ground and surges through the now open doorway. You move quickly toward the large floor-to-ceiling windows, as they are the most apparent escape. You barely squeeze through the 14-inch gap between the sill and the protective bars (there to keep patrons from falling out). You then slide halfway down a drainpipe before losing your grip and crashing to the ground. When you stand-up you are dazed, you hear the screams of your friends still inside the bar and you watch someone you don’t recognize jump from a window in flames. Then you hear a familiar voice, Rev. Bill Larson, cry out “Oh, God, no!” and turn just in time to see him burn to death, his body fused half-way out the window.

Rev. Larson’s body would be visible for hours as the scene was cleared. The image of his lifeless, doll-like appearance, frozen in a vain struggle for escape would haunt those who witnessed the tragedy for years to come. The disaster at the Upstairs Lounge was the deadliest fire in the long history of New Orleans, a city that has burned to the ground twice. It is also, perhaps, the greatest mass murder of GLBT folk in the history of the United States. Still, you most likely have never heard of it.

Jimmy, Eddie, and Inez were among the dead. Buddy survived, saving 20 others in the process, but his partner Adam didn’t. Luther made it out but later succumbed to his wounds. Over a quarter of the local MCC congregation also perished in the fire. The impact on New Orleans’ gay community was devastating. Yet, some people feel that the fire galvanized gay rights activists in the south and led to a new era of activism in New Orleans. Others still hold that it was nothing more than a tragedy that has been essentially forgotten.

The cause of the fire was never officially determined, but ask anyone who is familiar with the incident and they will tell you it was arson. They will even tell you the name of who set the blaze. The number one suspect, and really only suspect, was a hustler and troublemaker who had been tossed out of the bar earlier in the evening. Using some lighter fluid he bought from Walgreens he doused the steps and lit them on fire. He would later brag about this while drunk. However, he was never charged and eventually killed himself.

Is that why we don’t remember this disaster? Is it because the murderer was not a bigot determined to wipe us of off the face of the earth? Does his lack of a specific, prejudice driven, motivation make the horrific deaths of those involved less important to our community?

The remembrance of past tragedy is essential to the progress of any population. We might not be able to draw any direct lines to the Upstairs Lounge fire and ourselves today, but it would be silly to suggest that it had no impact on our movement. It might have led to revival of Southern activism or just been an essential part of the anger that would lead others to fight for change. Whatever the ultimate impact, June 24, 1973, and the people that perished, should not be forgotten.

I want to thank several current and former residents of New Orleans. Finding reliable information was difficult and at times the information was contradictory. Historian Roberts Baston and author Johnny Townsend both shared with me their research on the fire. The City Archives at the New Orleans Public Library provided access to source material. I also used information from James T. Sears’ book, "Rebels, Rubyfruit, and Rhinestones." I must also thank John Nicholson and the "NFPA Journal."

You can view news coverage of the fire at. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cvvRJNQolYM

_____________________________________________________________________________

No comments:

Post a Comment