May 3, 1976, Gainesville Sun, page 7D, Watergate: Minor Part of a Far Bigger Picture, by Howard Kohn, (Excerpted from Rolling Stone magazine)

(Editor's note: Was Watergate simply a weird outgrowth of some poor staff work, of a so-called "dirty tricks" mentality? In the following series excerpted from the forthcoming issue of Rolling Stone magazine, Associate Editor Howard Kohn details a chilling and awesome tapestry of events going hack to the 1930's that make the Watergate burglary, coverup and ensuing revelations minor scenes in a far bigger picture. A compelling and fascinating account which may well turn out to be one of the most important pieces of investigative journalism of the year.)

By HOWARD KOHN

From Rolling Stone

President Nixon's immediate answer to news of the Watergate burglary arrests was simple: The CIA, he told Haldeman (as recorded by the White House tapes) would close off the investigation because "if it gets out that this is all involved, the Cuba thing would be a fiasco it would make the CIA look bad and it is likely to blow the whole Bay of Pigs thing..."

Watergate, the Bay of Pigs, indeed a change of government in the Bahamas and a paint company going into real estate and gambling all were woven together, all rooted in a World War II alliance.

The year was 1942. The U.S. had just entered the war. The Department of War was worried that Nazi saboteurs were infiltrating the docks and shipyards along the East Coast. Already the Normandie, being converted to a troopship, had burned and sunk in her Manhattan berth.

Then a Navy officer suggested seeking help from the Mafia because of its influence in the dockworkers' unions. In short order Naval Intelligence struck a bargain with Meyer Lansky, top aide to the don of dons, Lucky Luciano.

Back in 1931 Luciano's hitmen had carried out a bloody purge of the Mafia's old guard to clear the way for his takeover. Then Luciano employed Lansky to modernize the Mafia's ingrown family structure. But in 1936 Luciano had been sent to prison with a 50-year sentence. Other leaders in the blood-oath Sicilian fraternity still considered the Jewish Lansky an outsider and, without Luciano around, balked at his innovations.

Lansky saw the Naval Intelligence deal as a chance to improve his position among the ruling lords of organized crime by opening prison gates for the don of dons. Lansky persuaded Luciano, still the power although operating from a prison cell, to have Mafia henchmen patrol the waterfront. In turn, Luciano was to be set free.

As New York City's Mafia-fighting special prosecutor, Thomas Dewey catapulted to the governor's chair by putting Luciano behind bars. But Gov. Dewey now agreed to the deal and transferred Luciano from Dannemora State Prison, known as "Siberia," to gentlemen's quarters at a prison near Albany. Then shortly after V-E day he signed the parole papers.

By then the Mafia had developed a working friendship with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the country's first autonomous intelligence agency, set up to oversee all wartime espionage. The OSS-Mafia deal, known as Operation Underworld, included gangland assistance for allied armies when they landed in Sicily.

But at the war's end in 1945 the OSS was disbanded, a move that dismayed both the Mafia and a circle of businessmen, politicians and espionage agents.

The men in this circle were from well-bred, well-educated backgrounds with connections at the highest levels of government and finance. Allen Dulles, a former topranking OSS official, and Gov. Dewey were two of their leaders both Wall Street lawyers, both on the opposite side of New York from Lansky and Luciano, both expecting top positions in Washington. One of their mentors was Dulles's brother, John Foster.

World War II had turned the U.S. into the world's most powerful nation. Dewey, the Dulles brothers and others had formed their circle in secret because they saw themselves as loyal and pragmatic Americans with a duty to help shape the country's new international role. Their project was to resurrect the OSS.

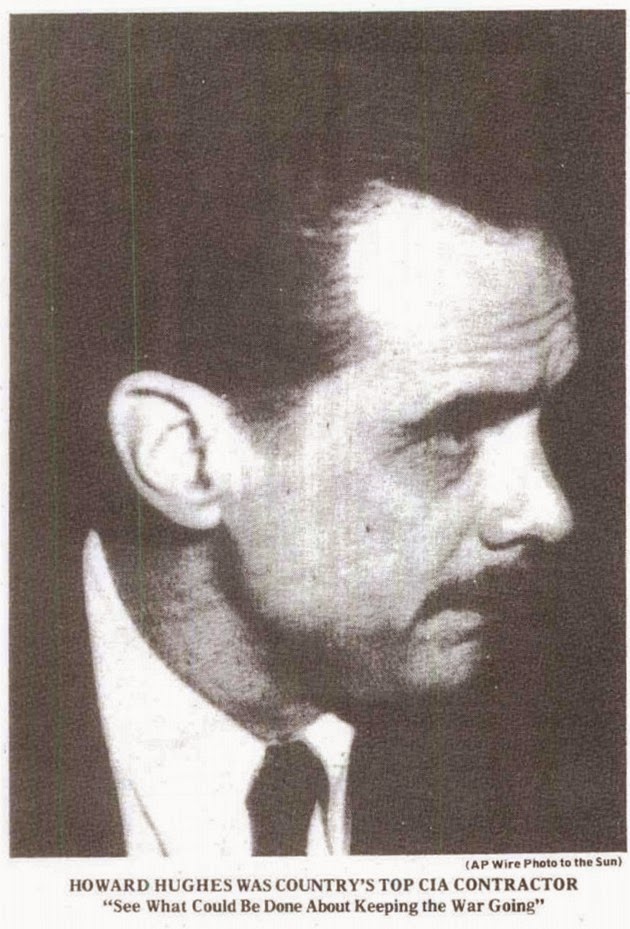

No country could stay on top, they believed, without a powerful and independent intelligence agency. Allen Dulles championed this idea among his contacts at the Pentagon and in the Truman administration. Truman appointed Dulles to head a three-member commission to study the U.S. intelligence system. Dewey and others in the circle lobbied Congress.

In July 1947, Congress passed the National Security Act. Truman signed it, as Dulles and Dewey had recommended, thereby creating the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) as a successor to the OSS.

The CIA was charged with protecting America by whatever means necessary. The Cold War had started. Communists were the new enemies. The Communist spread across the globe was to be stopped. To the Dewey-Dulles circle, some of whose members became key CIA officials, that meant the CIA was to be the patron of U.S. multinational companies which had set up in undeveloped countries.

The OSS's old partner, the Mafia, was among the leading multinational corporations that emerged in the late Forties. Lansky's moxie in freeing Luciano had impressed the Sicilian dons. Lansky also had outwitted Luciano, who was deported to Sicily immediately upon his release. But, with Luciano's unreserved blessing, Lansky took charge of domestic operations and finished the job the two had started a decade before. Lansky merged the Mafia's rival gangs into a conglomerate known as the

International Crime Syndicate, a network that Lansky estimated was "bigger than U.S. Steel," and which he immersed in banking, real estate. tourism and gambling.

At the same time, the exiled Luciano expanded the Syndicate's overseas connections. When Communist strikers shut down the French Port of Marseilles in 1947 and threatened to ruin American shipping, the CIA called on Luciano. He furnished hitmen while the CIA supplied money and weapons. After several murders the docks reopened for American shippers and also for the Syndicate's heroin smugglers.

Like the OSS, the CIA did not shrink from making deals with the Syndicate to preserve U.S. interests. Under the CIA's charter, such arrangements were legal.

Dewey and Allen Dulles also realized the CIA needed to safeguard its own political base to avoid potential power struggles in Washington, an analysis that carried the Agency into a clandestine role in American electoral politics.

What most concerned the CIA was the ephemeral mood on Capitol Hill. What the CIA wanted from Congress, aside from appropriations money, was to be left alone. In the opinion of the Dulles-Dewey circle, Congress posed the greatest danger to CIA autonomy. As a hedge against any difficulties, the circle began to collect Congressional goodwill for the CIA. Congressmen found their re-election problems eased — contributions, volunteers, endorsements — and their staffs peopled with bright young assistants introduced by members of the circle. Most favors went to young congressmen with a promising future, politicians who some day might be Capitol Hill leaders wad White House aspirants.

Richard Nixon, a member of the House of Representatives, was one recipient. In 1947 Dewey had recruited Nixon's vote to help establish the CIA. Dewey liked Nixon's amoral pragmatism and his fierce anti-Communism.

So in 1948, when Dewey saw a chance to embarrass Truman, to bolster the House Un-American Activities Committee (which Truman wanted to abolish) and to boost Nixon's career without publicly involving himself, he leaked secret CIA information on Alger Hiss to Nixon.

The Hiss case gave Nixon a national reputation. In 1950 he ran for the Senate against the popular Helen Douglas, calling her the " Pink Lady."

According to CIA sources, most of the information used by the Nixon campaign to label Douglas a Communist came from secret CIA files. He won easily.

In 1952, after only six years in politics, Richard Nixon became Vice-President. His nomination was shepherded through by Dewey. Having abandoned his own presidential ambitions, Dewey threw his support to Dwight Eisenhower. Then, at Dewey's request, Eisenhower picked Nixon as his running mate.

Immediately after the election Allen Dulles was promoted to the CIA directorship and his brother was named Secretary of State.

With Nixon as Vice-President and Dulles as CIA Director, the Justice Department in 1953 decided not to prosecute Lansky even though the IRS intelligence division found he was evading taxes, and in 1957 the Justice Department failed to carry through on an attempt by immigration authorities to deport him.

Throughout the Fifties the careers of Richard Nixon, Meyer Lansky and Allen Dulles prospered. But then the affairs of a little island in the Caribbean changed that and inextricably bound up the collective fortunes of the CIA, the Syndicate and the White House.

Lansky first visited Cuba in the fall of 1933 and befriended Fulgenaa Batista, an ex-army sergeant who had just ordained himself dictator. With Batista's sanction, Lansky opened several new casinos, the genesis of the Mafia's international gambling network.

With World War II the tourists stopped coming, Lansky shut down the Cuban gambling spas, and Batista encountered political turmoil. To stay in power he had to make concessions that extended Communist influence. U.S. corporations feared their Cuban investments might be nationalized. So in 1944, Naval Intelligence asked Lansky to pressure Batista into holding elections to keep out the Communists.

Lansky, a staunch anti-Communist, prevailed upon the dictator: elections were held, a pro-American candidate won and Batista left Cuba for eight years of exile in southern Florida.

During this period, on Capitol Hill the freshman Nixon was befriended by fellow Congressman George Smathers, a Miami playboy, and began socializing with southern Florida's fastbuck entrepreneurs. Among them were Richard Danner. a former FBI agent, and Charles "Bebe" Rebozo.

In March 1952, Batista returned from exile and resurrected his Cuban dictatorship in a bloodless coup set up by Lansky's $250,000 bribe to the elected president for his abdication. One month after Batista's return to power, Danner took Nixon on a tour of the Havana casinos.

Under the new Batista regime Lansky rejuvenated gambling in Cuba. He persuaded the other Syndicate leaders to invest heavily in a new concept: the hotel-casino.

In a few years the Syndicate's hotel-casinos in Havana were earning an estimated annual profit of $100 million.

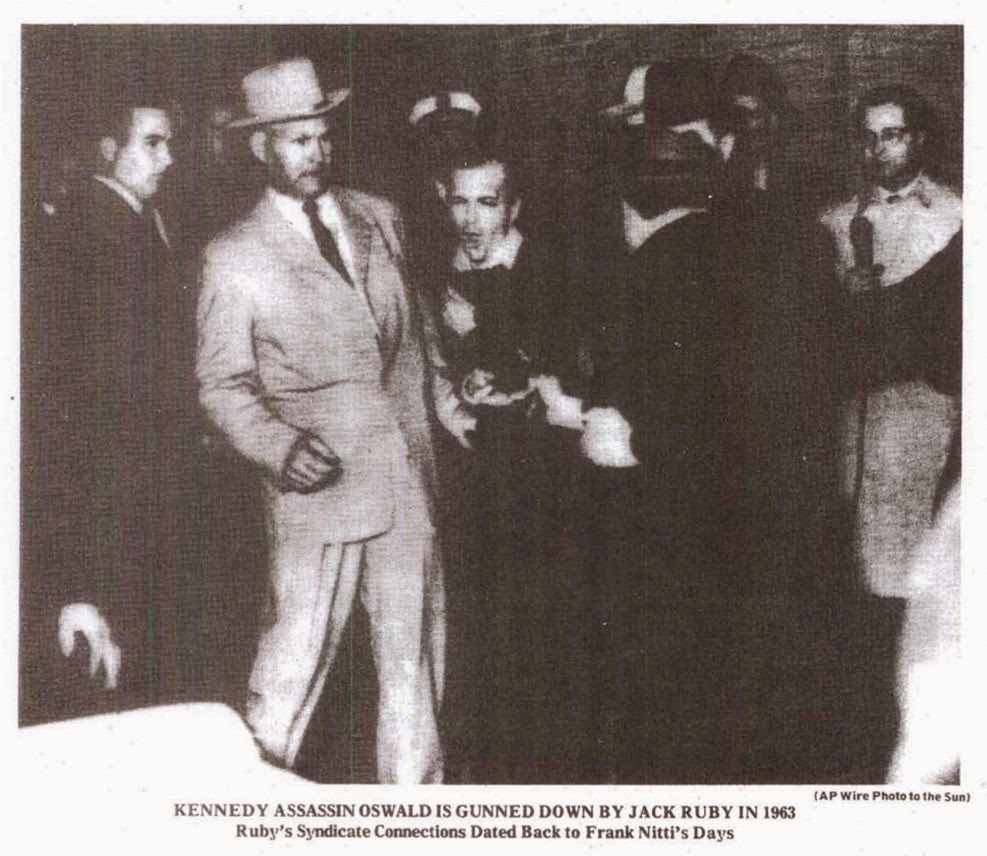

Meanwhile, by the mid-Fifties, Howard Hughes, sole owner of the country's largest privately held corporation, was also deeply enmeshed in the dynamics of money and politics.

Hughes had been accused of influence peddling during World War II in a Senate hearing involving a government contract. He considered himself a patriot and felt he had been unfairly singled out for practices standard to most defense firms.

Hughes began hiring ex-CIA employees as top administrators and eventually became the country's leading CIA contractor, a position that shielded him from federal prosecution and Senate hearings. Like the CIA and Lansky, Hughes also understood "quid pro quo" and electoral politics.

In early 1956, according to a former Hughes aide, the tycoon furnished Nixon with a secret $100,000 to help the Vice-President fight a dump-Nixon move by fellow Republican Harold Stassen.

Then in December 1956, Hughes loaned $205,000 to Nixon's brother Donald for a hamburger restaurant. The " loan" was never repaid.

Shortly thereafter, a Justice Department antitrust suit against Hughes was settled by a consent decree and the Hughes Medical Foundation was granted a tax exempt status that had been denied twice before, a status that saved Hughes an estimated $30 million a year.

During the next decade Hughes' interests continued to merge with Nixon, the CIA — and eventually with the Syndicate.

* * *

In 1958 a bearded ex-lawyer descended from Cuba's Sierra Maestra Mountains with a "Yankee-Go-Home" revolution. Lansky lieutenants smuggled in arms to help Batista, but Castro seized Havana on New Year's Day, 1959, and Batista and Lansky fled Cuba the same day.

At CIA headquarters in Langley, Va. the Agency began hatching plans to retake Cuba, partly to protect U.S. investments, partly to stop the spread of Communism, and partly because of the loss of the casinos.

Lansky had masterminded a system that allowed the Syndicate to skim winnings, evade taxes and launder illicit funds at the gaming tables. The CIA, according to Agency sources, had been using the same system to hide its payments to the underworld figures it sometimes employed.

Under the CIA plan, about 1200 Cuban exiles would land at the Bay of Pigs, steal through the jungle and establish a renegade government, thus providing a ruse for a full U.S. military assault against the Castro regime.

E. Howard Hunt, the CIA agent who recruited Cuban exiles for the invasion, later reported that Nixon was the Bay of Pigs "secret action officer" at the White House.

As the invasion neared, work began an a plot to demoralize Castro's forces by killing their leader.

The CIA eventually tried several times to murder Castro. It enlisted the help of Robert Maheu, an ex-FBI agent who had worked for the CIA under a special retainer since 1954. Maheu authorized to pay $150,000 for the hit, called on John Roselli, Sam Giancana and Santo Trafficante, all members of the Syndicate's ruling elite. President Johnson later discovered that "we're operating a damn Murder Incorporated in the Caribbean."

The assassination attempts failed, but they were not the only setback in the plan to retake Cuba. Richard Nixon had been defeated in the 1960 Presidential race, a turn that seemed to imperil the entire scheme. The CIA now had to obtain John Kennedy's support.

President Kennedy was presented the Bay of Pigs plan as a "fait accompli."

On April 17, 1961 — three months after he took office — the CIA army stormed the beach at the Bay of Pigs, only to be quickly muted by Castro's forces.

CIA officials told Kennedy Air Force bombers would have to provide air cover for the CIA soldiers. Kennedy refused.

Tension between Kennedy and the CIA next flared up in October 1962, during the Cuban missile crisis. Top CIA officials saw the crisis as a prelude to a second Cuban invasion and alerted the surviving Bay of Pigs army to stand ready. But Kennedy's negotiations with the Soviets produced an opposite result. The Soviets agreed to withdraw their missiles from Cuba, and Kennedy promised to end the U.S.'s undercover war against Castro (a promise he was unable to carry out).

As Kennedy moved toward a U.S.-Cuba rapprochement he came further into conflict with the CIA's unforgiving anti-Castroism. Finally, in mid-November 1963, he ordered his aides to get ready for a more thorough housecleaning of the Agency.

"The CIA will have to be dealt with," Kennedy told aides shortly before traveling to Dallas for a Nov. 22 motorcade. On that same day Kennedy's personal emissary opened talks with Castro in Havana. And, according to the Church Committee, the CIA also chose Nov. 22 to begin yet another plot to assassinate Castro - in continuing defiance of administration policies.

By the end of the day Kennedy's plans were dead with their patron in Dallas.

The Warren Commission attributed the Kennedy assassination to the personal derangement of Lee Harvey Oswald, whom they described as a pro-Castro zealot. A special counsel to the Warren Commission was Texas attorney Leon Jaworski, later to head the Watergate investigation.

Oswald, as a U.S. Marine in the late Fifties, held a top security clearance to a CIA-sponsored U-2 base in Japan. Shortly thereafter he defected to the Soviet Union, paying a $1,500 travel fare although his bank account held only $203. He claimed to be a Marxist, but the Soviets believed Oswald was a double agent for the CIA. After two years, Oswald returned to the U.S. and, despite his prior admissions of treason, was handed back his citizenship papers.

In the summer of 1963 Oswald surfaced in New Orleans as the organizer of a pro-Castro group with himself as its only member. He distributed pro-Castro leaflets, picked fights with anti-Castroists, and seemed to seek newspaper and TV coverage.

Oswald's pro-Castro leaflets were stamped with the address of a building used by the Anti-Castro Cuban Revolutionary Council, a CIA front group set up by Howard Hunt during the Bay of Pigs operation.

During this period Oswald was seen conferring with David Ferrie, who had worked for both the CIA and the Syndicate. The CIA had used Ferrie during the Bay of Pigs preparations to train pilots, and again in 1962 as an instructor in an anti-Castro camp outside New Orleans. At the same time, Ferrie was serving as a pilot and legal investigator for Carlos Marcello, a Syndicate leader in New Orleans.

In late summer, 1963, Ferrie called a Chicago phone number listed in the name of a young woman who on the day before Kennedy's death arrived in Dallas in the company of a man who met twice that night with Dallas nightclub owner Jack Ruby.

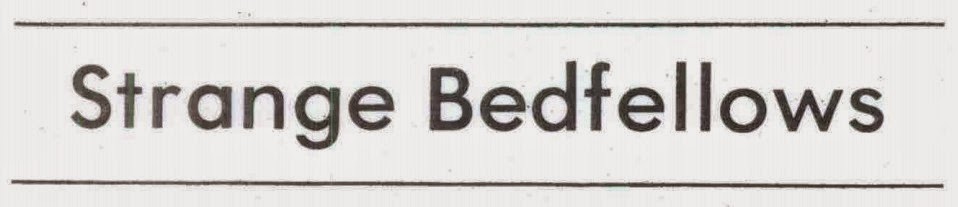

The next night, after Oswald's capture, Ferrie drove 1,000 miles to a Houston ice rink where he monopolized a pay phone for several urgent calls. Hours later Ruby went to Dallas police

(See CIA, Page 8D)

headquarters and gunned down Oswald.

In 1967 Ferrie was named as a conspirator in Kennedy's murder by New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison who announced he had uncovered an anti-Castro plot in the Kennedy assassination. Four days later Ferrie was found dead of a "brain hemorrhage." On the same day, a close friend of Ferrie who had gone on anti-Castro raids with him — E. del Valle — was found shot and hatcheted to death.

Garrison's case collapsed with Ferrie's death, Garrison claiming that Ferrie was going to turn state's evidence.

As for Ruby, at the age of 15 he was running errands in Chicago for Frank "The Enforcer" Nitti, heir to Al Capone's gangland empire. He became a small time hustler, then a top official in the Scrap Iron and Junk Handlers Union where two years later the union president was murdered. Ruby was held for questioning in the case, but not charged. Robert Kennedy later singled out that murder as a crucial step in the Syndicate's takeover of the Chicago union.

Ruby arrived in Dallas in 1947, a representative of the Syndicate's Chicago chapter, according to a Kefauver Committee attorney. He visited Lansky casino operator Lewis J. McWillie, a violent anti-Castroite, in Cuba in 1958 and in Las Vegas in October 1963. During October Ruby also made phone calls to others with Syndicate connections such as Paul Dorfman, Irwin Weiner and Barney Baker.

Three months after Kennedy's assassination, according to investigative reporter Tad Szulc, CIA agents met to plan a second invasion of Cuba. Howard Hunt, using the cover of a retired government official, was put in charge and a hitman was sent into Cuba on another Castro murder plot to precede the invasion. But the assassin was caught and the invasion plan eventually abandoned.

** *

By 1964 the Syndicate had lost interest in Cuba. Meyer Lansky had found a new home for the mob's offshore gambling empire in the Bahamas.

The Bahamas held some of the same attractions as Cuba - an easy plane trip from the mainland, hide-and-seek tax laws, the warm assurance of benign weather.

The political power in the Bahamas was Sir Stafford Sands, the Minister of Finance and Tourism and boss of the Bay Street Boys.

Lansky offered Sands $2 million in return for a Certificate of Exemption, a piece of legalese needed to operate a casino in the Bahamas. Sands. according to his own testimony, instead took $1.8 million in legal fees and the Syndicate got the Certificate. The casinos opened in 1964 to the attendant buzz of the international jet set.

But Sir Stafford's arrangement with the Syndicate became so blatant it angered local Bahamians. Cuba had proved the danger of betting everything on a man who no longer enjoyed popular support, so Lansky pulled another slick maneuver: he engineered his own revolution against Sir Stafford by having an aide become a secret informant and leak certain information about the Syndicate's deal with Sands.

The resulting scandal brought in a new "clean" government headed by Lunden O. Pindling. However, the Pindling campaign was financed by thousands of dollars from Lansky.

To complete the "housecleaning," Lansky's frontmen were removed and replaced by the Mary Carter Paint Co.

Mary Carter Paint was set up in 1958 by Thomas Dewey and Allen Dulles with $2 million in CIA money from Dulles, then CIA Director. During the Bay of Pigs operation, according to CIA sources, Mary Carter was a conduit for CIA payments to the Cuban exile army.

Soon it began buying land in the Bahamas and adopted a more conventional Caribbean name: Resorts International.

Resorts entered the gambling business in 1965 as partner with two Syndicate frontmen, but tried to appear separate and distinct from Lansky, rigorously applauding itself as an alternative to Syndicate gambling.

After 1966, Lansky's old frontmen disappeared from Vegas, just as they did in the Bahamas. The man who bought them out was Howard Hughes.

Within three years Hughes was Nevada's biggest employer with a payroll of $50 million. He owned a TV station, prime real estate and a string of hotel-casinos.

However, the Syndicate didn't step aside out of kindness, Instead, according to several sources, the Syndicate formed a partnership of symbiosis with the Hughes organization: providing the casino expertise while Hughes lent the necessary respectability.

While the Syndicate was rebuilding its gambling network, Richard Nixon was repairing his political career. In the fall of 1962, after his California loss, he took a vacation in the Bahamas. He then spent the next half-decade as a Wall Street lawyer renewing his political currency. In January 1968, he returned to the Bahamas as a presidential candidate and honored guest at the opening of a new Resorts International casino.

Nixon had met the Resorts board chairman, James Crosby, in late 1967, through Bebe Rebozo. Crosby kept an account at Rebozo's Key Biscayne bank. Watergate investigators subsequently felt the bank's major function was to abet a skim from Resorts. They did not prove the bank was laundering money for Resorts, but they did learn that Crosby had donated $100,000 to Nixon just before the 1968 New Hampshire primary, the pivot in Nixon's comeback.

According to the Senate Watergate Committee, Rebozo did serve Nixon as a courier and launderer of money kept in a secret White House cache shuttling these unattached funds through disparate bank accounts and then shelling them out to indulge Nixon.

By 1968 Hughes was close to becoming the world's richest man and Robert Maheu was ensconced as Hughes' "charge d'affaires" on a $520,000 annual retainer. In the spring of 1968 Hughes instructed Maheu: "I want you to go see Nixon as my special confidential emissary. I feel there is a really valid possibility of a Republican victory this year. If that could be realized under our sponsorship and supervision every inch of the way, then we would be ready to follow with Laxalt as our next candidate."

In December 1968, after Nixon's election, Maheu took $50,000 in $100 bills to Palm Springs and drove to the house where Nixon was staying and sent a consort inside. Apparently it was Hughes' intention that the money be delivered to Nixon personally, a risky procedure at which Nixon balked.

Maheu took the $50,000 back to Vegas and shortly thereafter Rebozo sought out Richard Danner, the ex-FBI agent who 20 years before had introduced Nixon to Rebozo. Rebozo discussed a donation; Danner took the message to Maheu who agreed to send the $50.000 to Nixon through Rebozo.

At the time Hughes had at least four favors in mind:

His lagging helicopter division faced loss of its major market if the Vietnam war ended. Hughes memoed Mallet, in early 1969 that "he should get to our friends in Washington to see what could be done about keeping the war in Vietnam going."

He wanted a halt in the Atomic Energy Commission's testing under the Nevada desert (these tests were subsequently moved to Amchitka Island off Alaska).

He needed White House approval before he could take over Air West Airlines. (Hughes received Nixon's personal go-ahead in 1969 at about the time the first $50,000— $10 bills cinched in bank wrappers and stuffed in a manila envelope — was delivered to Rebozo.)

He wanted antitrust laws waived so he could purchase the Dunes Hotel in Vegas, where he already owned six big hotel-casinos. Danner met with Attorney General John Mitchell three times in early 1970 and Mitchell gave the green light. Maheu then authorized the second $50,000, again carried to Rebozo by Danner in a manila envelope.

Three years later as Watergate closed in, Rebozo became alarmed the $100,000 from Hughes would be discovered. According to Nixon lawyer Herbert Kalmbach. Rebozo was worried because part of the $100,000 had been spent by Nixon's secretary and his two brothers.

Howard Hughes' $100,000 payment to Nixon's secret cache would almost certainly have stayed undetected if Hughes had not fired Robert Maheu in December of 1970.

For more than ten years Maheu had handled assignments for the CIA and for the Hughes organization. In the espionage, business, and criminal netherworlds his connections were invaluable.

But Maheu got caught up in an internal power struggle. Hughes was offered a chance to substitute Intertel, a firm with even better CIA contacts, for Maheu and to take over the casino operation in the Bahamas from Resorts, where investigators were beginning to uncover the Lansky ties. The Syndicate did not want a major investigation in the Bahamas; Hughes could provide a much better front

For Hughes it was a chance to put the western hemisphere's two premium gambling centers in his name. But the deal was good only if Maheu was eliminated.

Maheu's significance might have ended there. But Nixon came to view Maheu as a threat because the ex-aide's loyalties had been cut adrift and because he knew too much.

The IRS was asked to examine Maheu's bank account, to search for a tool of coercion — an indictment. Maheu reacted by taking information about the $100,000 Nixon transaction to Hank Greenspun, publisher of the Las Vegas Sun, who immediately talked to columnist Jack Anderson.

On Aug. 6, 1971, ten months before the Watergate burglary, Anderson's column described the bare details of the $100,000 transaction.

On Sep. 26, 1971, Greenspun cornered Nixon advisor Herb Klein and warned that the $100,000 could "sink Nixon."

In October, Greenspun was visited by Kalmbach, the Nixon lawyer, asking his knowledge of the $100,000. In February 1972, G. Gordon Liddy was given a go-ahead to scout prospects for breaking into Greenspun's safe. Liddy turned the job over to Howard Hunt, who met with Hughes security director, Ralph Winte.

Hunt, Liddy and Winte met in Los Angeles Feb. 19, but later claimed preparations broke down and that the robbery did not take place. (A White House tape has Ehrlichman saying it did and was successful, Greenspun says his office was broken into but that nothing was stolen.)

The Plumbers next focused on Democratic Party Chairman Larry O'Brien, who had been Hughes' chief Washington representative in 1969 and 1970 when the $100,000 took its journey. O'Brien had been hired by Maheu, and was dismissed along with Maheu. If Maheu had evidence about the $100,000, so might O'Brien.

According to Senate testimony, Mitchell authorized a second burglary — the burglary of O'Brien's office at Democratic national headquarters in the Watergate office building.

All the burglars were veterans of the Bay of Pigs operation. Now all were employed in the White House Plumbers unit and again their chief was Howard Hunt.

When Hunt, who claimed to have retired from the CIA in 1967, began working with the Plumbers on a "free-lance" basis, he was employed at the Mullen Agency, a public relations firm owned by Robert Bennett. Bennett, a Mormon and a friend of both Colson and Hunt, was asked to loan Hunt to the White House by Colson.

Bennett took a surprising interest in the White House's undercover activities and also was close to the Hughes people since he had been hired as their Washington representative, taking the place of Larry O'Brien.

Nixon's men apparently did not know about Bennett's other connections— he also was a CIA man.

The arrest of the Watergate burglars placed the CIA in an awkward spot. The men behind bars had demonstrable CIA backgrounds. Even more embarrassing was the CIA's careless outfitting of the Plumbers with agency equipment.

Most of the documentation that could have linked the CIA with the Plumbers was destroyed soon after the burglary. McCord's papers were burned, Helms disposed of all his taped Watergate conversations. But when prying reporters discovered that Hunt's confiscated paraphernalia contained CIA gadgetry, media suspicion about the CIA's role in the burglary leaped into headlines.

Reporters began pestering Hunt and the other Plumbers with unsettling questions. The burglars managed to maintain a professional silence. Then Bennett began holding audiences with a few of the media's most influential newsmen.

These newsmen began appraising the burglary as the dementia of anti-Castro partisans or, at the worst, the result of some unspecified political hijinks. They began to accept Bennett's word that the CIA had not been involved.

According to a CIA memo, Bennett also established a "back door entry" to the law firm representing the Democratic Party in a civil suit against the Plumbers, an opportunity he used to steer the investigation away from the CIA.

Two young Washington Post reporters, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, continued to do the Watergate story. Their persistence began to unnerve the CIA. So Bennett approached Woodward and according to the CIA memo "...has been feeding stories to Bob Woodward with the understanding there would be no attribution to Bennett. Woodward is suitably grateful for the fine stories and bylines he gets and protects Bennett"

Bennett, as a Colson confidante, was privy to several White House "dirty tricks" that were only tangential to the Watergate burglary, which he supplied to Woodward.

According to an ex-CIA operative familiar with Bennett and CIA infiltration of the White House, Bennett was acting on orders from CIA higherups in talking to Woodward. Bennett, who still enjoyed access to the White House, passed along everything he learned of the White House coverup to Woodward, the ex-CIA operative said. Eventually, according to the operative. Bennett assumed the code name "Deep Throat" and became the enduring catalyst for the Post's Watergate investigation.

Bennett scrupulously sheltered the Hughes organization from "Post" scrutiny. Woodward and Bernstein never learned of the Hughes-White House plan to burglarize Greenspun's safe.

Other CIA loyalists — Frank Sturgis and James McCord— joined Bennett in unraveling Nixon's ill-fated coverup while protecting the CIA.

At the same time Howard Hunt was demanding up to $1 million in White House money for his silence. Alexander Butterfield, who had once headed a Bay of Pigs rehabilitation program reportedly financed by the CIA, disclosed to the Watergate Committee that Nixon had taped all his Oval Office conversations, a turning point in the scandal.

Nixon was besieged. Public opinion was demanding he appoint a special prosecutor to investigate Watergate. Finally he chose Archibald Cox.

Within months his office was zeroing in on Rebozo's handling of the $100,000 from Hughes. Nixon sent word to Cox through Attorney General Elliott Richardson to lay off and when Cox refused, Nixon fired him in the "Saturday Night Massacre" that drained irretrievably the president's popular support.

Nixon then encountered escalating trouble from the new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski. A decade before Jaworski had been a special counsel to the Warren Commission and a director of a private foundation that laundered funds for the CIA.

The Jaworski-led Special Prosecutor's office found no illegalities involving the Hughes organization or the CIA. But it did indict Haldeman, Ehrlichman, Mitchell and others for their role in the White House covenup.

And the Special Prosecutor won a landmark Supreme Court decision that delivered the crucial White House tape recordings and produced incontrovertible evidence that Nixon had ordered the coverup. Faced with certain impeachment, Nixon resigned.

EPILOGUE

Allen Duties died in 1969 after spending his last years extolling the CIA in two books "The Craft of Intelligence" and "The Secret Surrender." Thomas Dewey died in 1971, his age and health having kept him from accepting the Supreme Court's chief justiceship offered by Nixon in 1969.

** *

Bebe Rebozo escaped indictment in the Watergate case despite strong circumstantial evidence of tax evasion and bribe taking. George Smathers, retired from the Senate, is prospering in Florida. Their old crony, Richard Danner, still works for the Hughes organization.

** *

Howard Hughes died at age 70 on April 5, 1976, from kidney disease. At the time of his death Hughes was earning $1.7 million each day from U.S. government contracts. Eighty Percent had been awarded without competitive bidding. Thirty-two were from the CIA, the most held by any single contractor.

** *

Because Robert Bennett's CIA cover was exposed by the Watergate scandal, he has closed down the Mullen Agency. He now works for the Hughes organization as a vice-president and CIA liaison.

** *

Meyer Lansky today lives undisturbed in Miami Beach. Now 72, he spends his time walking his dog and visiting with old friends. In December 1974 The New York Times printed a little-noticed story about Lansky It said that the federal government, in effect, has abandoned the effort begun by the Kennedys to put Lansky behind bars.

* * *

After three decades, the CIA's relationship with the Syndicate has not changed. When several Syndicate members went on trial in New York in 1971 for taking union kickbacks, the head of the local CIA bureau turned up in court as a character witness for the gangsters. Deportation proceedings against John Roselli were dropped in 1969 at the behest of the CIA.

(The Agency was embarrassed slightly in 1975 when the Senate CIA Committee discovered the Agency's alliance with the Syndicate in the Castro murder conspiracy. The scandal helped force out William Colby as CIA director.[)]

** *

Roselli and Robert Mahal testified before the Church Committee about their roles in the Castro Plot. But they only confirmed a scenario already known to Senate investigators. They did not elaborate on the expense of the CIA-Syndicate imbroglio.

Sam Giancana, however, did not get a chance to talk to the Senate Committee. On June 19, 1975, the day before his scheduled appearance, an assassin interrupted a late-night snack at his Chicago mansion with seven .22 caliber bullets. A few months earlier Richard Kane. the Giancana henchman who helped the CIA recruit its Bay of Pigs army, had been executed in a Chicago restaurant.

Another Syndicate figure, Jimmy Hoffa, was kidnapped and presumably killed on July 30, 1975, in Detroit.

** *

The Watergate investigation also has dissipated without full disclosure. Richard Nixon, now exiled to San Clemente, has never explained why he thought Watergate "would make the CIA look bad (and) blow the whole Bay of Pigs thing."

* * *

Nixon aide Chuck Colson, in 1974 remarks to a private investigator, described Nixon's fear of Hughes and the CIA and said: "The President and I talked about it one Sunday for about an hour and a half...I have seen CIA files. I know what's in them. I can't prove there was a conspiracy (to dump Nixon) but I would say that was the practical consequences of what they did.

"The excesses of the Nixon Administration were pretty bad. But what these guys are doing -- one doesn't justify the other — what these guys are doing is worse...The frightening thing is that there is nobody controlling the CIA. I mean nobody. I'll tell you one thing that scares me the most. They're all over the place. Almost everywhere you turn they've got their tentacles."

No comments:

Post a Comment